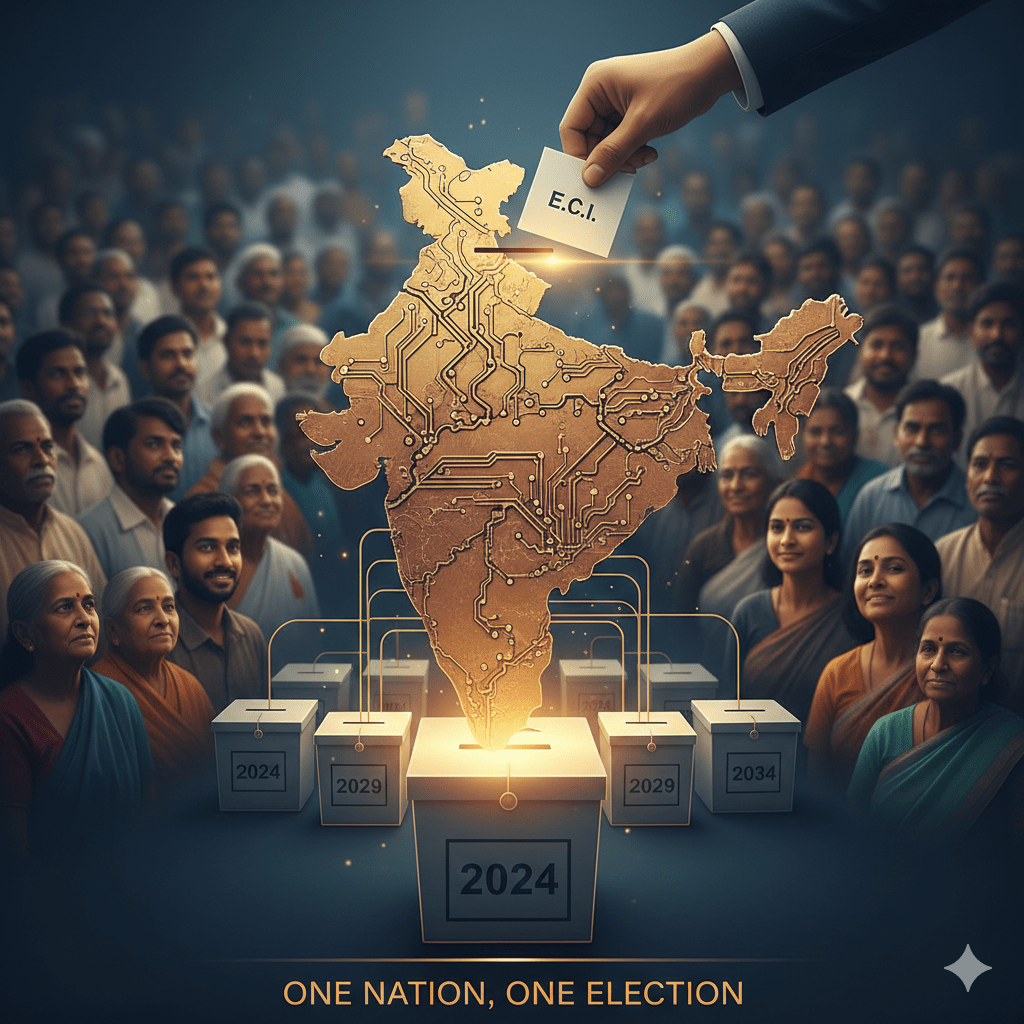

Reimagining the Republic—The Strategic Imperative of 'One Nation, One Election'

Quick Navigation

INTRODUCTION: Defining the Paradigm Shift

The concept of 'One Nation, One Election' (ONOE) refers to the synchronization of the electoral cycles for the Lok Sabha, State Legislative Assemblies, and Local Bodies (Panchayats and Municipalities) to occur within a singular window. Historically, India followed this pattern during the first four general elections (1951-1967) until the premature dissolution of several state assemblies disrupted the rhythm.

ISSUES: The "Why" Behind the Reform

The demand for ONOE has emerged due to several systemic bottlenecks that hinder India's "Vikasit Bharat" (Developed India) aspirations.

The frequent imposition of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC) creates a "policy paralysis." According to the HLC report, repeated elections force the executive to remain in campaign mode, delaying key developmental projects and administrative decisions.

The financial burden is astronomical. The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) estimated that the 2019 General Election cost nearly ₹60,000 crore. Frequent state elections add hundreds of crores to this tally, often leading to fiscal populism where states announce "freebies" to woo voters, straining the Debt-to-GDP ratio.

The massive deployment of Central Armed Police Forces (CAPF) for election duty diverts them from critical border security and anti-insurgency operations. The constant movement of these forces across the country incurs significant logistical costs and personnel fatigue.

Frequent elections often lead to "voter fatigue," potentially lowering turnouts. Furthermore, continuous campaigning can exacerbate communal and caste-based polarization as political narratives are constantly being refreshed for the next immediate poll.

IMPLICATIONS: The Multi-Dimensional Impact

The shift to a synchronized cycle carries profound consequences for the Indian federal structure and economy.

Fiscal Prudence: Synchronized polls could save the exchequer billions. A single electoral roll for all levels of government (Article 325) would streamline administrative costs. Enhanced Governance: With a fixed 5-year window, the government can focus on long-term structural reforms rather than short-term populist measures.

Federalism Concerns: Critics argue ONOE violates the "Basic Structure" of the Constitution. If a state government falls prematurely, the question of whether to impose President’s Rule (Article 356) or hold mid-term polls for the remainder of the term remains legally contentious. Political Homogenization: There is a risk that national issues might overshadow regional concerns. Research suggests that when elections are held simultaneously, there is a 77% probability of voters choosing the same party for both the Centre and the State (IDFC Institute). Constitutional Hurdles: Implementing ONOE requires amending Articles 83, 85, 172, 174, and 356, necessitating a two-thirds majority in Parliament and ratification by half the states.

INITIATIVES: The Roadmap to Reform

The government and institutional bodies have taken several steps to formalize this transition.

The Kovind Committee Report (2024) provided a comprehensive legal roadmap, suggesting an "Appointed Date" to synchronize the cycles.

The introduction of the One Nation One Election Bill (2026) in Parliament marks the first legislative attempt to institutionalize the "One Nation, One Identity" electoral framework.

Globally, countries like South Africa, Sweden, and Belgium follow synchronized election cycles successfully, providing a template for managing fixed-term legislatures.

In the S.R. Bommai Case (1994), the Supreme Court emphasized the importance of federalism, which remains a guiding light for ensuring that ONOE does not dilute state autonomy.

INNOVATION: The Way Forward

To make ONOE feasible and democratic, India must adopt forward-thinking solutions:

Leveraging AI and Blockchain for robust, real-time management of a unified electoral roll can prevent voter duplication and fraud.

Adopting the German model, where a government can only be removed if the legislature simultaneously agrees on a successor, can prevent the frequent collapse of governments and mid-term poll triggers.

If total synchronization is too rigid, a Two-Phase Election model (holding all elections in two windows every 2.5 years) could serve as a pragmatic middle ground, preserving the "accountability" function of frequent polls.

Strengthening the Election Commission of India (ECI) with permanent infrastructure at the district level (rather than borrowing from school staff) will ensure that the massive logistical scale of ONOE is manageable.

Conclusion: The DPDP framework is not merely a legal document but a Social Contract for the digital age. While the "Issues" of state overreach and compliance costs are significant, the "Implications" of empowered citizenship and data sovereignty outweigh the teething troubles. By embracing "Innovation" through PETs and sandboxing, India can demonstrate to the world that Privacy and Progress are not mutually exclusive.

5 KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Key Idea: Transitioning from "Competitive Populism" to "Productive Governance" via a fixed 5-year cycle.

- Key Term: Ex-ante Synchronization—the legal alignment of terms of the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies.

- Key Issue: The potential dilution of Regional Political Identity in the face of dominant national narratives.

- Key Example: The 1951-1967 period serves as a historical precedent proving that India has successfully managed simultaneous polls before.

- Key Fact: The cost of elections has risen from ₹11 crore (1951) to an estimated ₹60,000 crore (2019), necessitating urgent fiscal reform.

Probable Mains Questions

- "One Nation, One Election is a step towards administrative efficiency but poses a challenge to the spirit of federalism." Critically analyze. (250 words, 15 marks)

- Examine the constitutional and logistical challenges in implementing simultaneous elections in India. How can the German model of 'Constructive Vote of No-Confidence' offer a solution? (250 words, 15 marks)

UPSC Syllabus Mapping

GS Paper II Indian Constitution (Historical Underpinnings, Evolution, Features, Amendments); Functions and Responsibilities of the Union and the States (Federal Structure); Salient Features of the Representation of People’s Act.

GS Paper III Indian Economy (Fiscal Policy, Resource Mobilization).